International aid and development organisations are under scrutiny for how they go about trying to secure public donations. Some recent campaigns have prompted accusations of ‘poverty porn’. Are those accusations fair? And are the organisations themselves doing enough to clarify and justify their work? Jane Salmonson considers the issues.

Those who watched Comic Relief’s fundraising films for Red Nose Day this year will have seen Ed Sheeran visibly moved as he chatted to two young boys sleeping rough in a boat on a beach in Liberia. Or perhaps Ed wasn’t really moved at all. But in that case, he must be a talented actor as well as a talented musician. The film is recommended viewing for anyone interested in how poverty is portrayed for fundraising purposes.

Films like this give rise to allegations of ‘poverty porn’ because - it is argued - the viewer is encouraged to dwell on suffering and helpless victimhood, without really engaging with the more complex issues of context, and the structural causes of poverty. The film in question is accused of suggesting that it takes the ‘white saviour’ (as represented by our ‘everyman’ pop star, Mr Sheeran) to alleviate suffering, and disregards local peoples’ own resilience and abilities to cope.

‘Poverty porn’ is a catchy term, a nice piece of memorable alliteration, especially as the concept of ‘porn’ is now associated with passive, remote viewing for enjoyment without real human engagement. Think ‘food porn’, for example, to describe slavering over food programmes on TV without reaching for the pots and pans ourselves. Poverty porn is a term that could easily take further hold - beyond aid and development watchers - and spread more widely into the public consciousness.

‘Poverty porn’ is a catchy term, a nice piece of memorable alliteration, especially as the concept of ‘porn’ is now associated with passive, remote viewing for enjoyment without real human engagement.

Criticism of celebrity ‘do-gooders’ is also easy, although it will do the celebrities themselves very little harm. They can cry all the way to the bank. But another consequence of such criticism is that it can add fuel to the recent campaigns by elements of the media which are actively seeking to erode public support for aid and development. Whatever ‘porn’ in any of its forms actually is, we all know that porn is not nice. Designating fundraising appeals as ‘poverty porn’ thus gives people every reason to avoid responding to those appeals with donations, therefore undermining the appeals themselves.

So should we challenge usage of the term? Or accept that the criticism is sometimes justified, and act to change our approach to fundraising? Or perhaps a bit of both? To answer the question, it is worth looking at the facts. Comic Relief’s Red nose day is a made-for-TV biennial fundraising appeal, which has raised over a billion pounds for charities in the UK and in Africa since it started in the mid-1980s. Using celebrities and comedians has been integral to the idea from the start, so asking Ed Sheeran to take part was not in itself novel. Indeed, he joins a long list of well-known faces who prove, year after year, that viewers respond well to fundraising appeals endorsed by famous people on a TV programme which keeps them entertained whilst asking them for money.

Fundraising is a means to an end, not an end in itself. Comic Relief is said to have helped around 50 million people in the UK and Africa during its 30 year existence. The film clip of Sheeran drew criticism partly because of his reaction to the plight of the two young boys in Liberia, abandoned and sleeping rough, which was to try and arrange hotel accommodation for them whilst longer-term arrangements were put in place.

Our friendly boy-next-door pop star, with loads of money, seemed unable to accept that he couldn’t just buy solutions for these boys. Yet he displayed a reaction that I find entirely normal for someone exposed, perhaps for the first time, to life at the margins. As a very wealthy man, Ed Sheeran recognised that he had the means to buy a better life for his young interviewees without even noticing the dent on his bank balance. Good for you, Ed - stardom hasn’t removed your humanity!

However, I just wish that ending child poverty was that simple. Did the fact that he seemed disturbed by the boys’ lifestyle raise more money (and thereby enable more support to be given to projects helping street children) than if a local Liberian social worker had given us a calmer, more rounded, picture on air? We can’t know – but it most probably did. The fact is that fundraising is often more effective if the giver relates easily to the person asking them for money. Few of us know any Liberian social workers - but many of us feel that we know Ed Sheeran. We might thus ask: is it the critics who are being disingenuous, rather than the film-makers or the pop star?

The fact is that fundraising is often more effective if the giver relates easily to the person asking them for their money. Few of us know any Liberian social workers - but many of us feel that we know Ed Sheeran.

The problem with fundraising appeals like this is that they risk painting a one-dimensional picture encompassing the whole of Africa, ignoring the fact that the continent consists of fifty-four diverse countries. Within those countries, in varying degrees, income is being generated by farming and local businesses, not by international aid. Well-educated students graduate from African schools and universities. Entrepreneurialism thrives.

Yes, terrible poverty still endures amidst all that development, yet fundraising appeals focus only on the poverty. This can disguise the widespread advances made throughout Africa - by Africans - in building their own local health, education, and social services systems. It can also encourage us to overlook the effectiveness of longstanding African traditions, such as the roles played by extended family and community, which prevent vast numbers of children from falling into destitution, and helping them when they do.

I reach for the off switch on the radio when I hear Band Aid’s ‘Do they know its Christmas?’, which is played relentlessly, year after year. It was a thoroughly well-intentioned fundraiser written by Band Aid in 1984 in response to famine in Ethiopia. But its success has helped to distort our perceptions of the people of that vast continent in the decades since - and even today.

RUSTY RADIATORS

That brings us to the subject of Rusty Radiators. The Golden Radiator and Rusty Radiator awards were invented by the Norwegian Students and Academics International Assistance Fund in 2013 to celebrate the best, and the worst, of fundraising appeal videos. The idea came from the satirical ‘Radi-Aid – Africa for Norway’ video, which makes recommended viewing too. It is a parody, a reversal of the roles of donor and recipient, which shows African artistes coming together to raise funds to send radiators to the people of Norway, freezing in the winter snows. The film quite rightly challenges our often-facile perceptions of the vast African continent.

The Norwegian organisation presents an annual Rusty Radiator award to the ‘worst’, and Golden Radiator award to the ‘best’, fundraising appeal. ‘Worst’ films denote white saviours, helpless victimhood, and no context. This year’s Rusty Radiator award went to Ed Sheeran and Comic Relief. The Golden Radiator Award went to War Child Holland, for its film ‘Batman’, because it treated refugees as real people, with agency and dignity, despite their suffering.

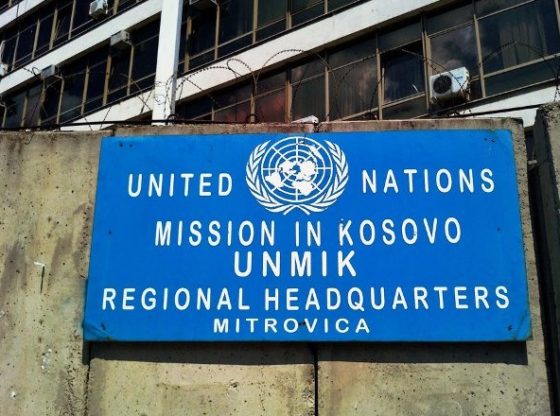

I welcome the attention recently drawn to these issues by the Norwegian Students and Academics. However, the Radiator Awards need to be seen in the context of the blurring of the lines between humanitarian and international development actions. These are not the same kinds of activities. The former encourages responses to alleviate the effects of disasters, both natural, such as famine in Ethiopia in 1984 and the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004, and man-made, such as the current refugee crisis caused by war in Syria. The latter seeks to elicit our support for developing countries’ development efforts. The former looks for short-term life-saving actions, and the latter for long-term improvements to the lives and life chances of people and communities in developing countries, now and in future generations.

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

International development is more complicated than humanitarian relief. The international community, under the auspices of the United Nations, worked long and hard at encapsulating its development aims and came up with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of seventeen goals which should be met by the year 2030. Scotland was one of the first countries to adopt the SDGs.

Within the framework of the SDGs, countries set out themselves what needs to be done within their own countries; in other words, what development actions need to be successfully implemented if they are to meet the goals. The SDGs are universal and apply equally to developing and developed countries. We in Scotland have targets and indicators to show whether or not we have met them, within our National Performance Framework and Scotland’s National Action Plan for Human Rights. The goals cannot be treated as ‘met’ unless they are met for everyone in society. No-one should be left behind.

The SDGs lend a new dignity to international development and a recalibration of the power balance between donor and recipient nations.

The SDGs lend a new dignity to international development and a recalibration of the power balance between donor and recipient nations. This helps donor nations to ensure that their development assistance falls within the SDG action plans drawn up by recipient nations. We don’t give through pity. We can see the development goals of other nations through the lens of our own struggles to meet our own development goals, and the commonly-held agreement to strive to meet the SDGs by 2030. Development assistance, professionally undertaken, can play a part in ensuring that the SDGs are met in poorer countries, as well as comparatively richer ones such as our own.

I think we need to challenge the usage of terms like ‘poverty porn.’ We live in dangerous times in which sustained campaigns, not only in the UK but elsewhere in the developed world, aim to turn people against international assistance, be it humanitarian or longer-term development support. A failure to respond to the critics of international assistance can be interpreted as silent acquiescence. If humanitarian relief and international development were better understood to be two very different activities - both of them very important - then the critics would have to work a bit harder to discredit either. We need to shout out the value of both humanitarian response and international development commitments.

Those of us who work in these areas should be prepared to take more time and trouble - especially in this time of short attention spans, ever-shorter soundbites, and rule-by-Twitter - to ensure that our publics are well-informed supporters of our work. We must communicate properly with them about what we do, of the value of the achievements which have been made, and not just reach out to them when we want their money.

Jane Salmonson is Chief Executive of Scotland’s International Development Alliance.

Feature image: Ed Sheeran campaigning with Comic Relief. Image: Comic Relief.