Tensions are simmering in and around the South China Sea. The region is of huge strategic importance due to the international trade that passes through it, and the resources which lie beneath. Various territorial disputes risk upsetting what is a delicate regional balance. Will this balance hold through 2018? Miguel Miranda examines the issues.

It’s hard to think of the waters between Vietnam and the Philippines as a battleground. Journalists have a habit of emphasising just how much global trade passes through the South China Sea, as well as the resources—abundant fish stocks and, possibly, dazzling quantities of oil—that could be exploited from its watery depths.

But if a shooting war over the South China Sea doesn’t seem apparent yet, it’s because in recent years the antiseptic language of diplomacy has softened the menace China poses to its weaker neighbours. The reailty is that the drama over the South China Sea is one of the most elaborate maritime showdowns in history.

SETTING THE SCENE

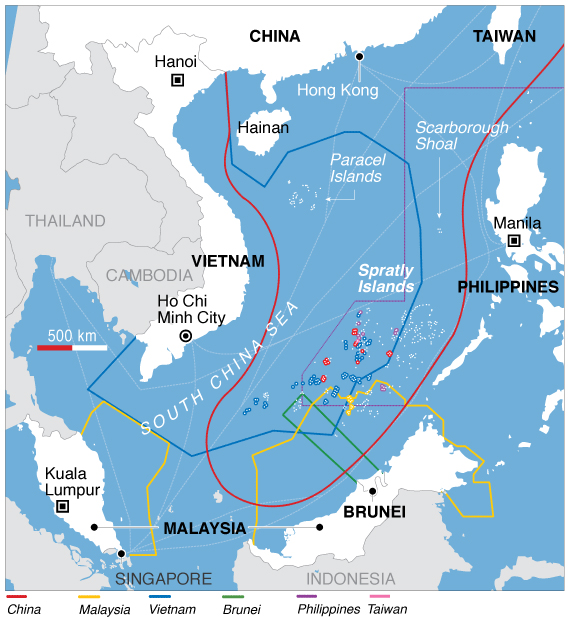

The struggle over possession of the sea dates to a little-known tiff between France - which had once cobbled a colonial dominion out of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos - and the Republic of China, between 1927 and 1949. But this tit-for-tat was one of maps and boundaries. The tension-filled 1930s saw imaginary dashes first appear in Chinese cartography as revisionist mapmakers did their best to translate the old British names for reefs and shoals in order to strengthen the nationalist government’s claims over its country’s nearby seas. This didn’t bother France too much - it had gone ahead and built outposts in two island clusters, the Paracels and Spratlys, to reinforce a dubious ‘annexation’.

The tension-filled 1930s saw imaginary dashes first appear in Chinese cartography. Revisionist mapmakers did their best to translate the old British names for reefs and shoals to give the Nationalist government legitimate claim over their country’s nearby seas.

After World War Two, the Soviet-backed Chinese Communists fought the Nationalist Kuomintang and emerged victorious in 1949, the year the People’s Republic of China (PRC) came to be. By the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the People’s Liberation Army had established the PRC’s present day borders, which included Hainan Island. The Paracel Islands (or Xi Sha) off the Vietnamese coast were seized without any complaints from the French, who were slowly losing their grip on Vietnam.

But from the 1960s onwards, China began to enlarge its control over the waters surrounding Xi Sha. By 1974, the Chinese navy had defeated the tiny South Vietnamese garrison in an atoll - a ring shaped coral reef - at the southernmost tip of the Paracels. Five years later, with Vietnam now unified, China launched an invasion to check Hanoi’s attempt to conquer Cambodia. In 1988, with Beijing and Hanoi squabbling over sandbars and shallows further south in the Spratly Islands, a Chinese frigate used its anti-aircraft guns to mow down Vietnamese sailors who had disembarked on a coral reef.

When the Association of Southeast Asian Nations - or ASEAN, which was founded by regional diplomats in 1967 - began to expand during the 1990s, a covenant known as the ‘Declaration On The Conduct of Parties In The South China Sea’ was slowly established as a conflict resolution mechanism. This would eventually be signed by all 10 member states, and China’s Vice Foreign Minister, in 2002.

A CAMPAIGN OF HARASSMENT

The situation seemed to improve in the early 1990s. The primary antagonists, China and Vietnam, were more focused on letting foreign investment pour into their economies. The optimism was short-lived, however. As China’s leadership transitioned from the grey eminence of Deng Xiaoping to the technocrat Jiang Zemin, its ‘peaceful rise’ was promoted. Some commentators even expected a demilitarisation of the South China Sea. But this was a calculated deception, and Chinese fishing vessels, along with unmarked patrol boats, soon started harassing fishermen in the waters around the Paracels and Spratlys.

Tensions rose to an unbearable level in 1998 when Chinese vessels drove away Filipino fishermen from Mischief Reef in the Spratlys. As similar incidents continued, Manila responded by letting the Philippine Navy beach an old amphibious transport on another feature, Scarborough Shoal, to serve as an outpost of sorts. This was meant to discourage further Chinese encroachment over the Philippines’ own Exclusive Economic Zone, which covered much of the Spratlys, where the Chinese had begun building their own remote outposts.

During the course of the 2000s, all of the claimants in the South China Sea built semi-permanent structures in the Spratlys. The Philippines had an airstrip and even a small hamlet on Thitu Island. Vietnam erected a multitude of guard posts. China built structures resting on steel and concrete pillars. But the oldest outpost in the Spratlys belonged to Taiwan, whose troops garrisoned a World War 2-era Japanese airstrip on the Itu Aba atoll it calls Taiping Island. Meanwhile, both Brunei and Malaysia traced their own claims over the Spratlys. Brunei’s was the least ambitious, being a rectangle extending from its tiny coastline.

China’s notorious large-scale island building began in 2014, a year marked by increased harassment directed at fishermen in the Spratlys. This aggression became so intense it forced a Filipino marine detachment to almost abandon their rusting hulk in Scarborough Shoal. The administration of then President Benigno Aquino scrambled for appropriate countermeasures; a hasty agreement was reached allowing the US Navy limited access to local bases while a case was filed with the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. Neither of these achieved their aims. With few options available, save for a meagre Mutual Defence Treaty with Washington DC in case of war, Manila’s stance on China’s encroachment of its waters has waxed and waned.

The current Duterte administration has chosen to ignore the Hague’s ruling from July 2016, which invalidated China’s bogus claims on the Spratlys. The Philippines is now committed to a less confrontational approach over the South China Sea, with no less than the Department of Foreign Affairs ingratiating itself with Beijing, from whom it hopes to secure generous financial largess that will fund Manila’s ambitious infrastructure projects.

Unfortunately there’s neither an essential text nor top-secret document that conveniently explains China’s behaviour towards its Southeast Asian neighbours. In fact, there doesn’t seem to be a definitive ‘master plan’ for the South China Sea at all.

Unfortunately there’s neither an essential text nor top-secret document that conveniently explains China’s behaviour towards its Southeast Asian neighbours. In fact, there doesn’t seem to be a definitive ‘master plan’ for the South China Sea at all. This is why it’s unhelpful to rationalise Beijing’s conduct as a quest for energy reserves or, at worst, a rightful annexation based on historical ownership. Whatever hydrocarbons there are underneath the Spratlys, China’s state-owned energy companies have never bothered to find and extract them.

As for historical claims, simply consider the farthest extent of the ‘Nine Dash Line’ that was invented in 1953 and traces an enormous loop from Hainan Island, forming what many have described as a tongue shape. It stretches until the edge of Malaysia’s coast to a completely submerged feature known as the James Shoal, which China insists is a reef. But it really isn’t. This imagined territory is so ridiculous to behold it isn’t surprising there’s an international furore over its existence.

DOES A CODE OF CONDUCT HELP?

During the ASEAN Summit, held in Manila from 12 to 15 November, the heads of state in attendance agreed on drawing up a new ‘Code of Conduct’ for de-escalating the South China Sea. Even President Donald Trump seemed conciliatory with his offer to mediate the dispute. But no single member of ASEAN has bothered to schedule a summit for hammering out this mysterious Code of Conduct which may, or may not, expand the scope of the same document from 2002.

On 11 January 2018, however, Cambodia—a non-claimant state—advocated for a binding Code of Conduct after it secured billions of dollars in new investments from Beijing. In what can only be understood as an underhanded response, neighbouring Vietnam announced it was allowing Indian firms access to its territorial waters on the same day. This elicited a terse comment from China’s zealous Foreign Ministry.

But would a genuine Code of Conduct mark the end of the South China Sea dispute? Hardly. Those seven Chinese islands in the Spratlys aren’t tourist attractions. The base on what used to be Fiery Cross Reef has enough runway for J-11 and J-15 fighter jets. The onsite accommodations can house at least a battalion of marines. The available satellite imagery from the AMTI reveals guard towers, bunkers, and radar installations in plain view.

What can the ASEAN states muster to thwart China’s footprint in the Spratlys? Indonesia and Vietnam have strengthened their navies with frigates and submarines, but these are nowhere near capable of taking on the Chinese Navy’s southern fleet. The leadership of the Philippines would prefer to drop the matter completely in exchange for better trade relations.

Optimism for the South China Sea is often misplaced. Those artificial islands aren’t going away and since 2017, Xi Jinping has instilled a new doctrine among his generals: they must ‘fight and win wars’.

So, unlike the darker episodes of the 1980s and 1990s, everyone’s playing nice this time - at least for now. But optimism for the South China Sea is often misplaced. Those artificial islands aren’t going away and since 2017, Xi Jinping has instilled a new doctrine among his generals: they must ‘fight and win wars.’ No wonder it makes better sense to view the South China Sea conflict the same way as the US Navy does - as a determined effort to break past the ‘first island chain’ formed by Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines, and allow China to project its military deeper into the Pacific Ocean.

This strange and confusing struggle for the South China Sea will continue until the bad faith and broken promises are replaced by fighter jets and cruise missiles. It’s a sobering forecast but China’s behaviour in its nearby waters was never cordial to begin with. One can still hope for the best possible outcome - the leaders of ASEAN certainly are.

Anyone hankering for an essential expert text on the topic should immediately settle for Bill Hayton’s The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power In Asia. Perusing Chinese state media isn’t recommended.

Miguel Miranda is a writer based in the Philippnes. He runs 21st Century Asian Arms Race, a website that monitors the geopolitical rivalry between China and India as well as current and potential conflicts in the Eurasian landmass. He is on Twitter at @helpfulmiguel

Feature image: US Defence Secretary Ash Carter and Philippine Defence Secretary Voltaire Gazmin tour the flight deck of the USS John C. Stennis in the South China Sea, April 15, 2016. Image: Air Force Senior Master Sgt. Adrian Cadiz. [CC]